I have never been a fan of change.

I once told my psychiatrist, “I hate change. I don’t handle it well at all, and it makes me incredibly anxious.”

She said, “But Sarah, life is all about change.”

“Exactly,” I said.

As in, “Yep. That’s why we’re sitting here together right now. That’s why we’ve gotten to know each other so well.”

If change is a freight train barreling unstoppably down its tracks, then I am an ant, unaware of our size deficit and standing valiantly with arms outstretched, trying desperately and hopelessly to stop it. It never works.

I find comfort in that which stays the same. I have a specific order that I never stray from at each restaurant I frequent. I wash and brush my hair in exactly the same pattern every time. I always take the same route to go the same places (although perhaps that has more to do with the fact that I’m the most directionally challenged person I’ve ever met). I love watching the same shows over and over and over again so that I can find solace in laughing in all the same places. I am made anxious by a change of plans, a change of scenery, a change of routine.

So the first time someone said to me, “You will never be the same after this. Good, bad, or indifferent, your grief will change you,” I felt the urge to dig my feet in and solidify them with concrete.

I don’t want to change. The seasons can change, we can buy new pens when the ink runs out, we can maybe even try a new coffee flavor. But I don’t want the fundamental things about myself, whatever those may be, to change.

Truthfully, I never felt more myself than when I was expecting our daughter. I have known for many years that my primary goal in life is to be a mother, and once I saw that goal coming to fruition, I felt an all-encompassing comfort I’d never felt before in my own skin.

But who am I, who will I become, now that I am a babyless mother? A part of me did die with her, though I’m not sure yet which part. That makes me nervous, too.

I fear becoming the woman who only ever weeps, the one who people spot from across a restaurant and think to themselves, “God, it looks like she’s been crying for ages. How long has it been since she slept?” I fear becoming the woman who cannot feel happiness for others expecting daughters. I fear becoming someone who isn’t myself—someone who doesn’t love hot coffee year-round, who doesn’t love to get lost in a book, who doesn’t laugh at Ross saying “PIVOT” no matter how many times it’s been heard before, who doesn’t love tight hugs, who doesn’t want to be the biggest cheerleader for her loved ones. I fear becoming someone who can’t, won’t, doesn’t mother her children.

Most of all, I fear the inevitable changes of who I am because watching them wash over me feels like sprinting blindfolded down a dead-end tunnel.

But like I said: change is a train, and I am an ant. I can’t stop it, and like it or not, I have already seen myself shift some. I’m trying to take on the changes gracefully.

For instance, I’m more anxious now than ever before about my loved ones. I’m concerned that a (perhaps metaphorical, perhaps literal) meteor could fall out of the sky and pluck any one of them, or all of them, away from me at any time.

I’m concerned about the time that I have left on this earth. I’ve learned the hard way this summer that life is too precious, too fragile, and too short to be wasted. But how do you rage against that lesson when all you want to do is grieve and cry in bed? How long will those days last? When will sunshine feel good on my skin again?

I feel softer than I did before. I already considered myself an empathetic person (read: I am an emotional sponge. Whatever you are feeling—happiness, sadness, anger—I am guaranteed to feel it, too). But now, I find myself realizing over and over that so many things I once cared so much about no longer matter to me. All I want is family and time with them—mine, Daniel’s, ours. My cares have been simplified.

I also feel myself leaning into my faith more than I ever have. People have commented how proud they are of both of us for doing so, but truthfully, how does one survive their child’s death without believing that somewhere, somehow, with someOne, their child is happy and safe? I feel the same way about people’s tendency to comment on what they perceive to be our strength. What choice do we have?

More than anything (and perhaps this will be my lifeboat as I continue to feel myself changing): I notice a pride that I’ve never felt before. I noticed it the moment my daughter was placed in my arms—a world-shifting, heart-swelling, everlasting kind of pride that causes everything else to fall away. I have never been prouder of anything in my life than I am of her. I have never been prouder of Daniel than I am of him as a father. I’ve never been prouder of myself than I am as her mother.

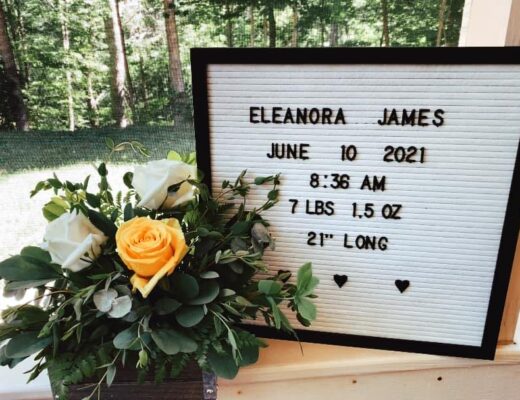

I know I will continue to change, much as it makes me anxious. We both will. But I hope the changes will be mostly good. More than anything, I hope we are and continue to be parents that Eleanora is proud of.

I saw a post the other day that said something along the lines of, “I hope that when my child looks down at me from Heaven, she gathers her friends around, points at me with pride, and says, ‘That’s my mama.'”

I hope you do, baby girl. I hope your papa and I make you proud every single day, even as we grow and change. The one thing that will never, ever change: how much we absolutely love you.